Putting several “best” peach ripening techniques to the test

I’ll admit that I’m a bit of a peach snob. A perfectly ripe, juicy, sweet, fragrant peach is among the foods I consider exceedingly edible, while I dismiss unripe, green, crunchy peaches as a tart travesty. And don’t get me started on canned “peaches”! Although I love peaches, I’m often hesitant to purchase them hard and unripe from the store because I’m afraid that I’ll end up with a mealy mess. Is there a good way to reliably ripen a peach? As the inaugural experiment on VegEdibles, I decided to scratch beneath the fuzzy surface of peach ripening techniques.

What do we know about peach ripening?

Before getting into the various peach ripening techniques, let’s review the fundamentals of peach ripening.

- Peaches are a climacteric fruit, meaning that they continue to ripen after being picked from the tree. Other climacteric fruits include bananas, apples, tomatoes, and other stone fruits like plums.

- Ethylene is a plant hormone that is released as a gas and triggers a cascade of physiological changes associated with climacteric fruit ripening.

- As fruit ripens, it becomes sweeter (due to the conversion of starch to sugar), softer and less green (due to changes in the cell wall and the production of color compounds), and more fragrant (due to the production of volatile compounds) (see Wikipedia article on ripening).

- In California, peaches are typically picked after ethylene production has triggered the ripening process. Therefore, ethylene exposure is not necessary for fruit ripening, and peaches are ready to eat once they have softened.

That’s nice, but what do I do with my hard peaches?

I had heard about ripening fruit in a paper bag, but I decided to tap into the collective wisdom of the Web to find the best way to ripen a peach. It didn’t take long before I stumbled upon a popular blog post describing the best way to ripen peaches. This technique involves placing the peaches stem side down between two cotton tea towels. And the peaches must not touch one another or be disturbed in any way. For obvious reasons, I will refer to this as the “pampered peach” method. The author claims that this method is superior to the “paper bag” method, which he believes causes the fruit to rot or become mealy. But so many others swear by the paper bag method. And what about just leaving them out on a plate?

Designing a peach ripening experiment

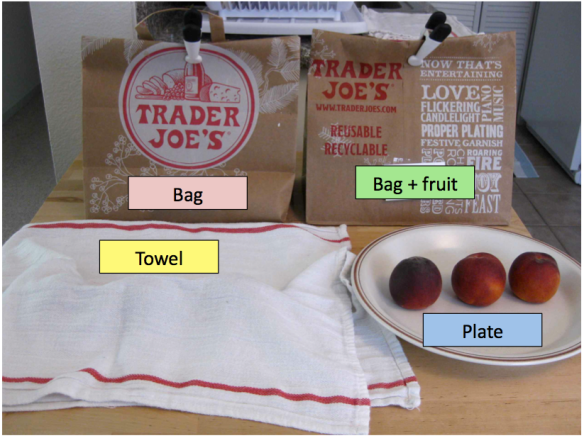

I found the “pampered peach” method intriguing, but I wanted to determine whether it was worth it to go to that much trouble. Therefore, I decided to compare the “pampered peach” method with three other common methods for peach ripening. Here are the four methods I tested:

- The “pampered peach” (Towel) method: This method, as described above, involves placing the fruit stem side down on a table between two cotton tea towels. And, of course, the peaches must be set apart from one another to obey the “no touching” rule.

- The “paper bag” (Bag) method: Basically, the fruit is left in a closed paper bag to promote ethylene accumulation. (Some web sources claim that this hastens ripening.) I placed the peaches stem side down and apart from one another to enable direct comparison with the “pampered peach” method.

- The “paper bag with a fruit friend” (Bag + fruit) method: This is a modification of the “paper bag” method. The addition of ethylene-producing fruit, such as an apple or banana, is purported to further hasten the ripening process. I placed the peaches stem side down and apart, as in the “paper bag” method, and I added an apple and a banana to the bag as well.

- The “fruit bowl” (Plate) method: This is my default fruit ripening method and was somewhat of a control to see whether the other methods were superior.

I purchased 12 equally firm California peaches from Trader Joe’s and randomly assigned them to the four ripening conditions.

The peaches were placed on a table in their respective ripening environments. They were observed daily for signs of ripeness and were evaluated for taste once they were judged soft enough to eat.

Ripening results

Bill kindly volunteered to blindly judge the ripening process, so every night I set out the peaches in a line (in random order) and he judged their ripeness.

We used three ripeness indicators to judge the peach ripening process:

- Firmness: Bill gently pressed the flesh surrounding the stem in a few different places. He assigned each peach a relative firmness score. In general, the peaches started off uniformly hard and softened slowly over the course of a week. I took the average of Bill’s firmness scores from days 3-6 for the graph below. As you can see, there was little difference in firmness between the peaches, although the “Bag + fruit” group had the two most firm peaches as well as the softest peach.

- Smell: Although Bill attempted to score the degree of fragrance of each peach, it turns out they were too similar to rank. Generally, we observed that the peaches started off with minimal fragrance and became very fragrant after a week. Interestingly, Bill was able to consistently identify peach #11, which was in the bag with fruit, because he claimed that it smelled like a banana. However, he did not identify the other two peaches that were in the bag with the banana, and peach #11 was not any closer to the banana than the other two peaches. I could not smell the banana on peach #11, suggesting that Bill has superior smelling abilities.

- Color: Bill judged the color of the peaches by looking at the skin surrounding the stem. Generally, the peaches turned from green to orange/yellow over the course of a week (see peach #2 below as an example). Using color change as a measure of ripening, there was no major difference between the peaches as far as the speed or quality of ripening.

Tasting results

It turned out that most of the peaches had softened and seemed ripe enough to eat a week after the start of the experiment. A few seemed harder and less ripe, but it made sense to taste them all at once and see whether the less ripe ones were from a particular group.

Bill and I both took on the formidable task of tasting the peaches. To make this a blind taste test, I placed peach slices (a quarter of a peach per sample) into randomly assigned positions in two muffin tins. Bill’s muffin tin had a different arrangement than mine so as to prevent influencing each other’s scoring. We tasted the peaches, taking note of important ripeness indicators such as sweetness and juiciness.

WARNING: Eating three peaches in one sitting is not recommended, as it can wreak havoc on the digestive system. Enough said.

After tasting the peaches, Bill and I independently ranked them from sweetest/most ripe to most tart/least ripe. Here are the key findings:

- As you can see from the rankings below, we were in reasonable agreement. Considering the peaches that we ranked in our top half, we were in agreement for five out of six.

- There was no clear winner as far as ripening methods go. We both found peach #8 (paper bag method) to be the sweetest, but peach #5 (also paper bag method) was toward the bottom of the rankings for both of us.

- We both ranked two of the three peaches from the plate, towel, and bag methods among our top half.

- Interestingly, we both ranked all three peaches that had been ripened in a bag with fruit among our bottom half.

What can we learn from this peachy experiment?

As you may recall, since peaches are typically picked after ethylene production has triggered the ripening process, ethylene exposure is not necessary for fruit ripening. Nonetheless, a cursory Internet search will reveal that it is widely recommended to ripen peaches in a closed environment to promote the trapping of ethylene gas. This process is often purported to accelerate fruit ripening, although I couldn’t find solid evidence to back this claim. I decided to put this fuzzy logic to the test.

The results were a mixed bag (no pun intended). The bottom line is that there was no clear winner among the ripening methods, although the “bag + fruit” method produced the least desirable peaches in this experiment. I’ll end this post by addressing some important questions for my fellow peach lovers who actually made it to the end.

- Can I buy hard peaches and expect them to ripen in two days? The peaches I bought were very hard and took about a week to soften regardless of the ripening method. They were still hard after two days and only began to soften after 3-4 days. They weren’t actually ready to eat until days 5 or 6. So, if you need a peach to be ripe in two days, you should probably buy one that is already somewhat soft.

- Can you tell from the color of a peach whether it will become sweet? Probably not. Peaches #2 and #8 started out quite green, but were ranked among our sweetest. On the other hand, peach #5 started out yellow/orange, but it was much less sweet.

- Can you tell from the firmness of a peach whether it will taste good? Again, probably not. Two peaches in the bag with fruit (#9 and #11) were the most firm and #6 (also in the bag with fruit) was the least firm, and all three were not very sweet.

- Is it a good idea to eat three peaches in one sitting? No. Definitely not.

Love this experiment and glad you choose my towel technique as one to try. You two are kitchen scientists for sure. Fun to read and interesting findings. Here’s to sweet peaches all summer.

Thanks for stopping by and reading about our experiment! I’ve been enjoying your site. And Boz and Gracie are so cute!

Nice to see that you are putting your PhD to good use.

Dad

I’ve noticed a real difference between stone fruit from a store and the farmer’s market. Probably owing to the fact that they are delivered in big trucks and large pallets, I think they deliver harder fruit to stores. Trader Joe’s in particular is pretty secretive about where they are sourcing fruit from. You’re lucky if it says the state of origin, but beyond that forget it. Whole Foods generally indicates at least the farm they are from. This is most useful for direct comparison, because many of the same farms also say at local markets. I too have found that stone fruit can take many days to ripe. In contrast, market peaches need no more than 1-2 days. Other notable differences are the the store peaches tend to be slightly larger (perhaps due to perceived desires of store shoppers) and when ripe not quite as flavorful or sweet.

Good points. I recently bought a couple of white peaches from Sprouts, and they ripened on my counter within a couple of days (and tasted great). I’ll have to try the peaches from the farmers’ market. I’m definitely not too keen on buying the hard Trader Joe’s peaches anymore. I’m still really curious whether ethylene from apples and/or bananas can actually hasten the ripening of peaches. So many people swear by it, but it just didn’t seem to make a difference when I tried it.